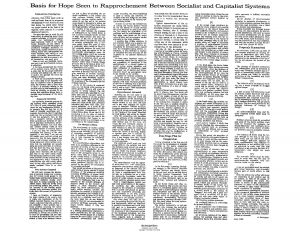

The Essay That Helped Bring Down the Soviet Union

Op-Ed: The New York Times

It championed an idea at grave risk today: that those of us lucky enough to live in open societies should fight for the freedom of those born into closed ones.

By Natan Sharansky, Mr. Sharansky, the author of “The Case for Democracy,” is a former spokesman for Andrei Sakharov. He spent nine years in Soviet prisons and the gulag.

Fifty years ago this Sunday, this paper devoted three broadsheet pages to an essay that had been circulating secretly in the Soviet Union for weeks. The manifesto, written by Andrei Sakharov, championed an essential idea at grave risk today: that those of us lucky enough to live in open societies should fight for the freedom of those born into closed ones. This radical argument changed the course of history.

Sakharov’s essay carried a mild title — “Thoughts on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom” — but it was explosive. “Freedom of thought is the only guarantee against an infection of mankind by mass myths, which, in the hands of treacherous hypocrites and demagogues, can be transformed into bloody dictatorships,” he wrote. Suddenly the Soviet Union’s most decorated physicist became its most prominent dissident.

For this work and other “thought crimes” the Soviet authorities stripped Sakharov of his honors, imprisoned many of his associates and, eventually, exiled him to Gorky.

In 1968, when this work was published, I was a 20-year-old mathematician studying at the Moscow equivalent of M.I.T. Although we dared not discuss it, my peers and I lived a life of double-think: toeing the Communist Party line in public, thinking independently in private. Like so many others, I read Sakharov’s essay in samizdat — a typewritten copy duplicated secretly, spread informally and read hungrily.

Its message was unsettling and liberating: You cannot be a good scientist or a free person while living a double life. Knowing the truth while collaborating in the regime’s lies only produces bad science and broken souls.

Sakharov’s essay, which coincided with the Prague Spring, helped energize democratic dissident movements that were just budding in a post-Stalinist world. The largest of these was one I would soon join: the so-called refusenik movement to allow the Soviet Union’s long-oppressed Jews the freedom to emigrate.

Sakharov’s essay, which coincided with the Prague Spring, helped energize democratic dissident movements that were just budding in a post-Stalinist world. The largest of these was one I would soon join: the so-called refusenik movement to allow the Soviet Union’s long-oppressed Jews the freedom to emigrate.

Some Russian dissidents mistrusted the Zionist movement as particularistic and unpatriotic, fearing it would distract from their broader human rights agenda. Not Sakharov. He supported the refuseniks because he recognized the right to emigrate as a gateway to democratic entitlement that opens everyone to embracing freedom in a closed society.

By the mid-1970s I was serving as Sakharov’s spokesman, and I remember after yet another friend of ours had been sentenced to prison, he told me: “They want us to believe there’s no chance of success. But whether or not there’s hope for change is not the question. If you want to be a free person, you don’t stand up for human rights because it will work, but because it is right. We must continue living as decent people.”

Sakharov’s decency made him a moral compass orienting not just the East, but also the West. He insisted that international relations should be contingent on a country’s domestic behavior — and that such a seemingly idealistic stance was ultimately pragmatic. “A country that does not respect the rights of its own people will not respect the rights of its neighbors,” he often explained.

As Sakharov and his fellow dissidents in the 1970s and ’80s challenged a détente disconnected from human rights, Democrats and Republicans of conscience followed suit. Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan disagreed about many specific policies, but both presidents linked human rights and foreign policy. President Carter treated Soviet dissidents not as distractions but as respected partners in a united struggle for freedom. President Reagan went further, tying the fate of specific dissidents to America’s relations with what he called the “evil empire.”

As Sakharov and his fellow dissidents in the 1970s and ’80s challenged a détente disconnected from human rights, Democrats and Republicans of conscience followed suit. Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan disagreed about many specific policies, but both presidents linked human rights and foreign policy. President Carter treated Soviet dissidents not as distractions but as respected partners in a united struggle for freedom. President Reagan went further, tying the fate of specific dissidents to America’s relations with what he called the “evil empire.”

Approaching the fight to win the Cold War as a human rights crusade as well as a national security priority energized Americans. It reminded them that, regardless of the guilt and defeatism of the Vietnam War or the shame and cynicism of Watergate, the country remained a beacon of liberty.

This anniversary of Andrei Sakharov’s heroic essay comes during similarly dark days for the United States.

Despite the dramatic discontinuities between Donald Trump and Barack Obama, in divorcing human rights from foreign policy President Trump is following President Obama’s lead.

Mr. Obama repeatedly prioritized engaging dictatorial regimes rather than challenging their human rights records. His eagerness to strike a nuclear deal with  Iran muffled his moral voice during Iran’s Green Revolution of 2009. And he refused to make diplomatic progress conditional on demands that Iran stop supporting terror globally or executing its own people at home.

Iran muffled his moral voice during Iran’s Green Revolution of 2009. And he refused to make diplomatic progress conditional on demands that Iran stop supporting terror globally or executing its own people at home.

Mr. Trump has taken America’s human-rights-free foreign policy to absurd new heights. His assertion that North Koreans support Kim Jong-un with “great fervor” undermined America’s moral standing, sabotaged North Korean dissidents and legitimized an evil dictator. His shocking refusal to confront President Vladimir Putin of Russia over his country’s blatant interference in the 2016 United States presidential election highlights his unwillingness to protect Americans’ democratic rights, let alone Russians’ human rights.

The wisdom of Sakharov’s essay may not be in fashion these days, but the truth it contains is eternal. People all over the world are waiting for an American leader to recover it.

Natan Sharansky, the author of “The Case for Democracy,” is a former spokesman for Andrei Sakharov. He spent nine years in Soviet prisons and the gulag. This essay was written with Gil Troy, a historian at McGill University and the author of “The Zionist Ideas.”