Cambodia’s economy in the post-EBA era

Op-Ed: East Asia Forum, 16 December 2019

Author: Pheakdey Heng, Enrich Institute

It has been yet another impressive year for Cambodia’s economy. Thanks to continued strength in traditional sectors such as garments, tourism, trade and construction, Cambodia’s GDP grew 7 per cent in 2019 — the highest growth in the ASEAN region according to the IMF.

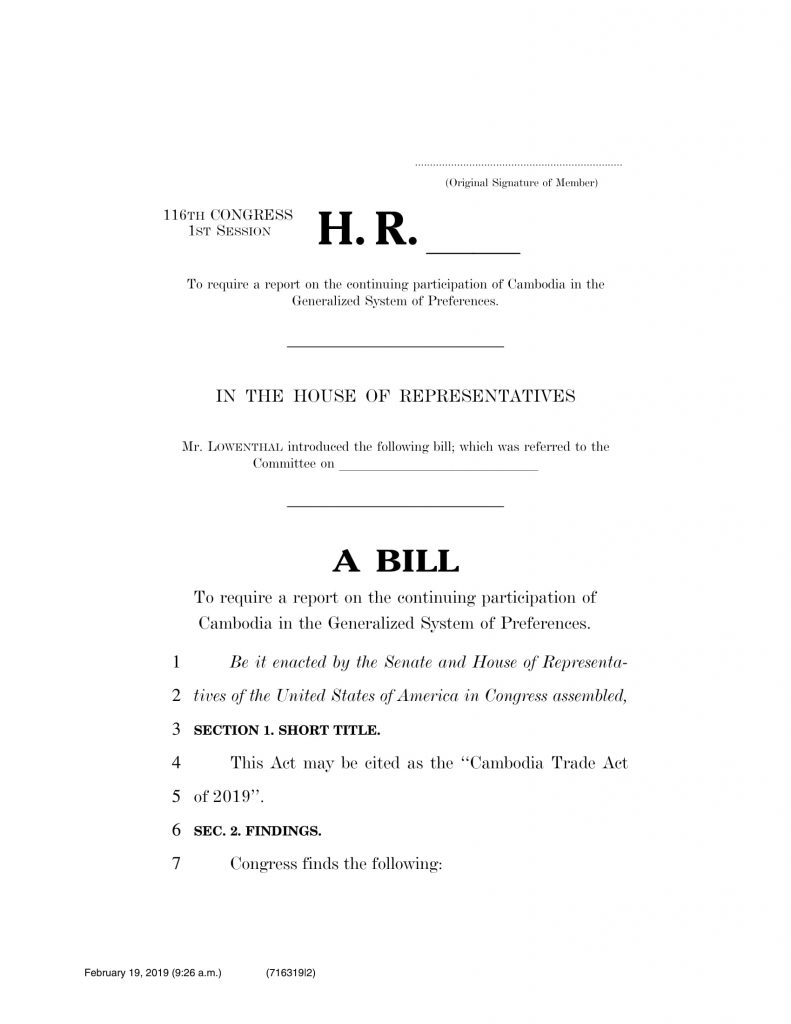

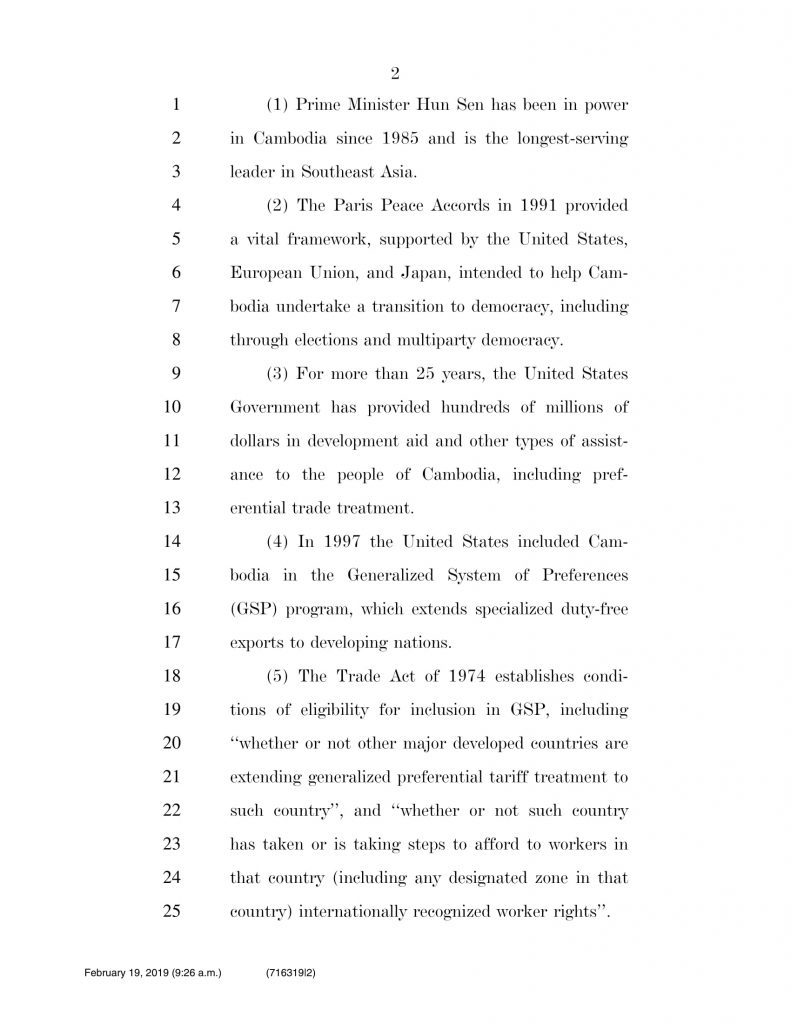

While this impressive growth is a reason to celebrate, the possible withdrawal of the EU’s Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative may affect Cambodia’s growth prospects for 2020 and beyond. Established in 2001, the EBA gives Cambodia and 48 of the world’s poorest countries access to zero tariffs on all exports except arms and ammunition to the European Union on the condition that they comply with the principles of 15 United Nations and International Labour Organization conventions on core human and labour rights.

The European Union launched an EBA withdrawal procedure on 12 February 2019 after citing ‘a deterioration of democracy and respect for human rights’ in Cambodia. After a six-month monitoring and evaluation period, the EU Commission issued a report on the situation in November and gave the government a month to respond. Depending on developments in the country, the Commission will decide by February 2020 whether or not to suspend Cambodia’s EBA privileges fully or in part. A suspension would come into effect by August 2020.

EBA termination will be a big economic loss for Cambodia, currently the second-largest beneficiary of this trade privilege. Cambodia’s exports to the European Union last year totalled around US$5.8 billion — 95 per cent of which entered the European Union duty-free.

The textile industry will be hit the hardest. The EBA has fuelled an export boom that has kept the economy growing at a steady 7 per cent a year and helped to lift millions of people out of poverty. Suspending the EBA makes exports less competitive, putting workers at risk of losing jobs and dragging down economic growth overall. Around 2 million Cambodians depend on the textile industry, including 750,000 employees.

To help cushion the negative impact of the EBA withdrawal, the government is introducing measures to facilitate trade by lowering logistical costs, cutting red tape and supporting businesses with a six-day reduction in the number of public holidays to increase productivity.

Around US$3 billion is reserved for fiscal stimulus to cope with the potential slowdown. The government also plans to increase revenue raised from taxation, customs and excise by more than 20 per cent next year. The government collected some US$4.57 billion in revenue from customs and taxation in the first nine months of 2019.

While Cambodia is almost certain to miss out on growth potential, the EBA withdrawal is also an opportunity to implement deep reform to ensure sustainable growth over the long term.

Currently Cambodia’s main exports are garments and footwear, mostly to the European Union and the United States. But this industry is labour-intensive, has low levels of technology application and low value addition. Cambodia needs to transform its industrial structure from a labour-intensive sector to a technology-driven, knowledge-based modern industry if it wants to generate lasting growth.

The strategic approach is to promote the development of the manufacturing and agro-processing industries. Investment in these sectors is more sustainable than the low-wage garment industry. It can enable Cambodian workers to acquire higher skills, paving the way for higher value products and services and better integration into regional and global production chains.

To build economic resilience, Cambodia also needs to diversify its economic partners. Trade with China, Japan and South Korea has been on the rise and there is still room to grow. Cambodia and China are now discussing a free trade agreement. If successful, it sets a good precedent for bilateral FTAs with other countries.

Economic diversification and modernisation can only be achieved with the support of hard and soft infrastructure, a constructive policy and political environment and strong human capital. Investment is needed to improve the availability, reliability and affordability of energy, to develop a multimodal transport and logistics system and to strengthen the labour market through skill development. Political stability, good governance and sound regulation are also essential to attract foreign investment and technology transfer.

Continue reading