CORONAVIRUS: WHAT WE KNOW SO FAR

Original source: CambodianInterpreter.Org Video Clip Original Link

What is this virus?

The virus has been identified as a new type of coronavirus. Coronaviruses are a large family of pathogens, most of which cause mild respiratory infections such as the common cold.

But coronaviruses can also be deadly. SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome, is caused by a coronavirus and killed hundreds of people in China and Hong Kong in the early 2000s.

Can it kill?

Yes. Over 2850 people have so far died after testing positive for the virus.

What are the symptoms?

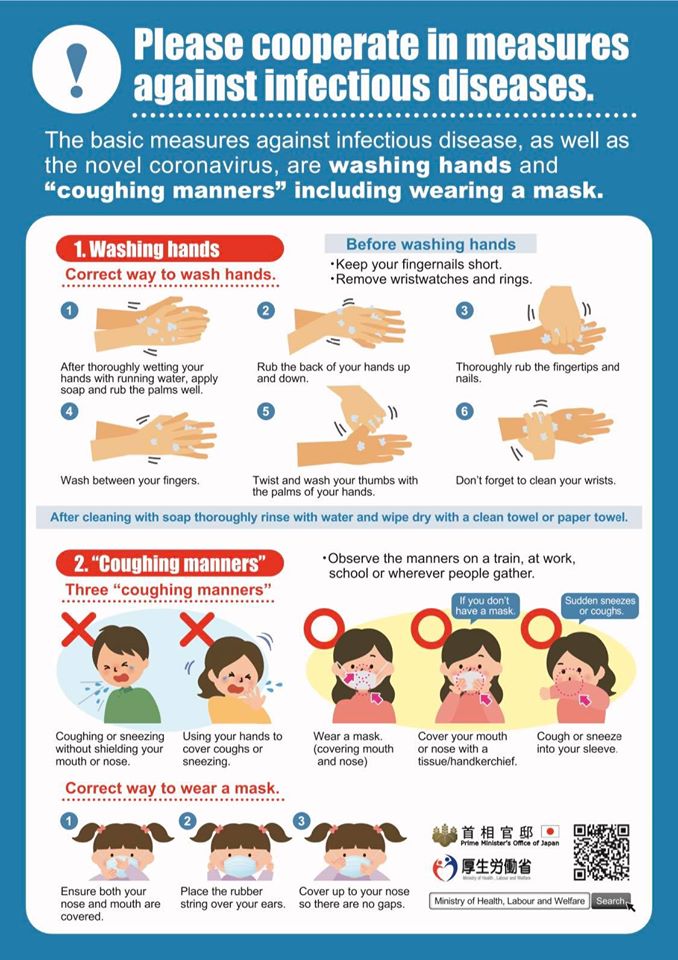

Its symptoms are typically a fever, cough and trouble breathing, but some patients have developed pneumonia, a potentially life-threatening infection that causes inflammation of the small air sacs in the lungs. People carrying the novel coronavirus may only have mild symptoms, such as a sore throat. They may assume they have a common cold and not seek medical attention, experts fear.

How is it detected?

The virus’s genetic sequencing was released by scientists in China to the rest of the world to enable other countries to quickly diagnose potential new cases. This helps other countries respond quickly to disease outbreaks.

To contain the virus, airports are detecting infected people with temperature checks. But as with every virus, it has an incubation period, meaning detection is not always possible because symptoms have not appeared yet.

How did it start and spread?

The first cases identified were among people connected to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan.

Cases have since been identified elsewhere which could have been spread through human-to-human transmission.

What are countries doing to prevent the spread?

Countries in Asia have stepped up airport surveillance. They include Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines.

Australia and the US are also screening patients for a high temperature, and the UK announced it will screen passengers returning from Wuhan.

Is it similar to anything we’ve ever seen before?

Experts have compared it to the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The epidemic started in southern China and killed more than 2850 people in mainland China, Iran, South Korea, Italy, Hong Kong and elsewhere.

=====

កូរ៉ូណាវីរុស៖ អ្វីដែលយើងត្រូវដឹង

តើមេរោគនេះជាអ្វី?

វីរុសនេះត្រូវបានគេកំណត់អត្តសញ្ញាណថាជាប្រភេទមេរោគឆ្លងថ្មី។ កូរ៉ូណាវីរុសគឺជាគ្រួសារវីរុសបង្កជំងឺដ៏ធំមួយដែលភាគច្រើនបណ្តាលឱ្យមានការឆ្លងមេរោគតាមផ្លូវដង្ហើមស្រាលៗ ដូចជាផ្តាសាយធម្មតា។

ប៉ុន្តែកូរ៉ូណាវីរុសឬវីរុសឆ្លងនេះក៏អាចមានគ្រោះថ្នាក់ផងដែរ។ ជំងឺ SARS ឬរោគសញ្ញាផ្លូវដង្ហើមធ្ងន់ធ្ងរបណ្តាលមកពីវីរុសឆ្លងនិងបានសម្លាប់មនុស្សរាប់រយនាក់នៅក្នុងប្រទេសចិននិងហុងកុងនៅដើមទសវត្សឆ្នាំ ២០០០ ។

តើវាអាចសំលាប់មនុស្សបានទេ?

ត្រូវហើយ។ មនុស្សជាង២៨៥០ នាក់បានស្លាប់បន្ទាប់ពីបានធ្វើតេស្តិ៍រកឃើញវីរុសនេះ។

តើរោគសញ្ញាអ្វីខ្លះ?

Continue reading