ជាការសង្ខេបការតែងតាំងលោកនេត សាវឿន ជាប្រធានសហព័ន្ធសហភាពបាល់ទៈកម្ពុជាគឺក្រៅពីមានទំនាស់ផលប្រយោជន៌ធ្ងន់ធ្ងរនិងខុសក្រមសីលធម៌នៃសហព័ន្ធ លោកនេត-សាវឿនត្រូវបានសមាជិកគណកម្មាធិការសើររើតំណែងនេះឡើងវិញពីព្រោះលោកមានប្រវត្តិបាតដៃប្រឡាក់ឈាមជាច្រើនក្នុងតួនាទីលោកជាមេបញ្ជាការប៉ូលីសជាតិម្នាក់។ លោកជាមនុស្សស្និតបំផុតការពារអំណាចផ្តាច់ការអោយលោកហ៊ុន-សែន ហើយក្នុងអត្ថបទស៊ើបអង្កេតរបស់អង្គការឃ្លាំមើលសិទ្ធិមនុស្សពិភពលោកក្នុងចំណងជើងថា ជនបាតដៃប្រឡាក់ឈាមទាំង១២នាក់ លោកនេត-សាវឿនធ្លាប់វាយដំអ្នកដើម្បីសួរចំឡើយ បាញ់រៈសម្លាប់មនុស្សក្រៅច្បាប់ ដឹកនាំកំឡាំងសំខាន់ធ្វើរដ្ឋប្រហារឆ្នាំ១៩៩៧ គ្រប់គ្រងមនុស្សអន្ធពាលបាតដៃទី៣គំរាមកំហែងសមាជិកបក្សប្រឆាំងនិងមនុស្សនៅក្នុងបក្សក៏ដូចចាគាបសង្កត់ប្រព័ន្ធតុលាការ និងបញ្ជាកំឡាំងផ្ទាល់ខ្លួនអោយចាប់លោកកឹម-សុខា ប្រធានគណបក្សសង្គ្រោះជាតិដាក់គុកក្រោមបទចោទដែលលោកនេត-សាវឿននិចោទជាបន្តបន្ទាប់ថាក្រុមបដិវត្តព៌ណ។

Cambodian volleyball federation president ‘ran death squads’ during late 90s, report claims

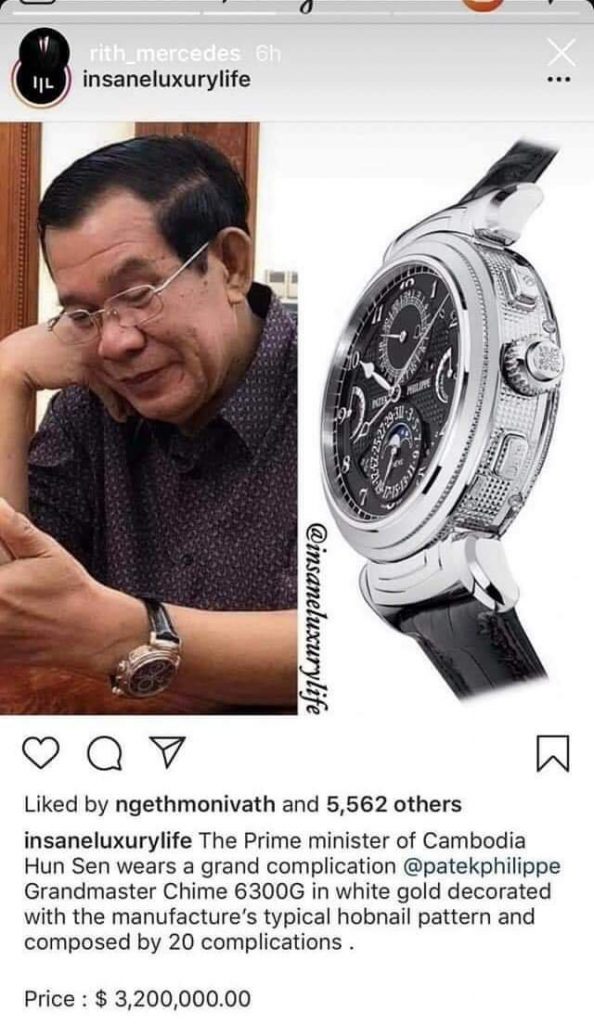

Neth Savoeun, president of Cambodia’s volleyball federation and the national police commissioner, allegedly presided over extrajudicial killings during the centralisation of power under prime minister Hun Sen

- Op-Ed: Independent

- Jack Davies

Volleyball’s international governing body, FIVB, is facing calls to sever ties with the president of the Cambodia national federation after The Independent learned he stands accused of presiding over extrajudicial killings and torture.

The man in question, Cambodian national police commissioner and volleyball federation president Neth Savoeun, was among eleven other senior generals christened Cambodia’s “Dirty Dozen” in a Human Rights Watch report last year. The report highlighted their role in propping up Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen, who has governed the country in one guise or other since 1984. In service of maintaining the premier’s grip on power, all 12 participated in and ordered serious human rights abuses, according to the report.

While FIVB said it was “important not to pre-judge” the allegations against Savoeun, it promised to review them following publication of this article.

Should the case be referred to FIVB’s ethics panel, which has full investigative and decision-making powers over the affairs of its member federation officials, it could prove damaging to the sport in Cambodia. Despite its best team ranking 387th globally, the country has become a regular feature on the beach volleyball circuit, hosting a leg of the World Tour earlier this month.

It also comes at a fractious time for Cambodian foreign relations. Recent years have found its government at odds with the United States and European Union after it disbanded the country’s main opposition party, the CNRP.

Savoeun has been a key political ally and enforcer of Hun Sen’s since his earliest days in power, having risen swiftly through the ranks of post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia’s police force. Speaking to the Lawyers Committee for International Human Rights in 1984, a former police colleague put Savoeun’s rapid ascension down to his bloodthirstiness.

“[He] became a big shot because he was so awfully brutal at interrogation. He even shot people during interrogation,” the former colleague said. “Sometimes, when he is bored, he will call someone in for a beating just for fun.”

What interest would somebody so allegedly brutal have in the gentle sport of volleyball? Cambodian-American political scientist Dr Sophal Ear is a leading authority on his homeland. Ear believes the police commissioner’s position with the volleyball federation fits the pattern of patronage networks that define much of Cambodian society.

“If you own a volleyball team and you’re going to enter international competitions, there’s going to be travel, training, hotels involved. That’s serious money and they can’t expect the players to find sponsors, so their sponsor will be in the military and Neth Savoeun will be the godfather of it all,” Ear said. “You took money from them, so you owe them. They gave you a gift and now you’re in their pocket. That’s how it works.”

Savoeun is not the only member of the Dirty Dozen to take an active interest in sport. When not deputy supreme commander of Cambodia’s armed forces, General Sao Sokha is also president of the country’s football federation.

In 1997, already more than a decade in power, Hun Sen’s fragile alliance with the Cambodian royalist party, FUNCINPEC, looked set to fall apart. Rather than call elections, the prime minister launched a bloody coup in which both Sokha and Savoeun acted as field commanders, the Human Rights Watch report alleges.

It was not until 2008 that Savoeun attained his current role as national police commissioner, taking over the position following his predecessor’s death in a helicopter crash.

Continue reading