Weekly Analysis:

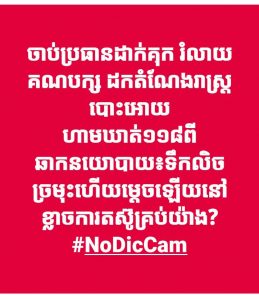

But pragmatists have advised that you couldn’t expect the jailed President to revoke your democratic CNRP back to live. The jailed President has no freedom to exercise his free will as well as to undertake a routine leadership to oversee his over 3 million members organization effectively. It has no proof that a jailed person could be an effective leader for any active large political organization. There must be a big misunderstanding in this matter, and the sympathizers have likely played into Hun Sen’s trap.

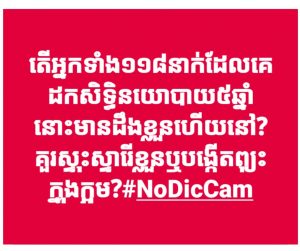

What would I begin with for the current political affairs of Cambodia? At all times, it is a challenging moment for major scholars to analyse the Cambodia political situation in a structural manner. Cambodia politics, during these decades, has been unpredictable, uncertain and risky. Hun Sen has become a pivotal actor to all these unpredictable occurrences and he has boldly coped all those occurrences. In July 1997, the bloody coup detat was exploded within his controllable magnitude, but the anchoring force at the border by his opponent led by Nhek Bun Chay was believed to pressure him to return back to conduct a participatory election. Thus, this happened only after he was sure to ably cope the election outcome. This end of 2017, the preparedness for Senate election in February 25, 2018 and the national election in July 29, 2018, Hun Sen has been pragmatic on his predictable election outcome as if he allowed the existing rule of the game (existing NEC and CNRP), he would loss the power. Hun Sen has learnt to be a King in all circumstances (from his own speech and it is true from our own observation through his lifetime of politician career; this is different from other leaders who have stepped down when time is suitable for them to step down for the sake of collective/national interest although they still see chance to win over the game). This time, Hun Sen has made a decisive moving-ahead by jailing Kem Sokha (president of the CNRP), dissolving the CNRP, taking away all seats of both 55 law-makers and 5007 commune/quarter counsellors elected by the people, and banning all 118 high ranking officers of the CNRP not to participate in Cambodia politics for 5 years. This political manoeuvring has noted as a cold blood coup to renew his power. Hun Sen has been the longest premier serving in post by a facade democratic election, and he has boasted to stay tenure for another ten years.

What would I begin with for the current political affairs of Cambodia? At all times, it is a challenging moment for major scholars to analyse the Cambodia political situation in a structural manner. Cambodia politics, during these decades, has been unpredictable, uncertain and risky. Hun Sen has become a pivotal actor to all these unpredictable occurrences and he has boldly coped all those occurrences. In July 1997, the bloody coup detat was exploded within his controllable magnitude, but the anchoring force at the border by his opponent led by Nhek Bun Chay was believed to pressure him to return back to conduct a participatory election. Thus, this happened only after he was sure to ably cope the election outcome. This end of 2017, the preparedness for Senate election in February 25, 2018 and the national election in July 29, 2018, Hun Sen has been pragmatic on his predictable election outcome as if he allowed the existing rule of the game (existing NEC and CNRP), he would loss the power. Hun Sen has learnt to be a King in all circumstances (from his own speech and it is true from our own observation through his lifetime of politician career; this is different from other leaders who have stepped down when time is suitable for them to step down for the sake of collective/national interest although they still see chance to win over the game). This time, Hun Sen has made a decisive moving-ahead by jailing Kem Sokha (president of the CNRP), dissolving the CNRP, taking away all seats of both 55 law-makers and 5007 commune/quarter counsellors elected by the people, and banning all 118 high ranking officers of the CNRP not to participate in Cambodia politics for 5 years. This political manoeuvring has noted as a cold blood coup to renew his power. Hun Sen has been the longest premier serving in post by a facade democratic election, and he has boasted to stay tenure for another ten years.

There are speculations that Hun Sen will turn Cambodia into North Korea model in the next five years under modern stage of the international stresses. He will not oblige to follow democratic model well-known among Western states, or he will imitate governance model of China or Vietnam. He will practice facade-democracy through a disenfranchised and controllable election mechanism to ensure his tangible political projection.

Pragmatically, the strongest Hun Sen doesn’t exactly reflect its reality, the strongest Hun Sen is because the weakness of his rivalry (opposition). As said, during the largest crowd of rally against election rigs in 2013 by the CNRP, the negotiation with Hun Sen seems achieved trivial things such as the new creation of NEC structure and the TV Channel, while the key components for power-based sustainability such as the reform or change of judiciary system/institution as well as the neutral arm-force, neutral policemen, and neutral public servants etc. were not prevailed. After agreeing to resume the national assembly and endorse Hun Sen as Premier in his fifth mandate, there were notably conflict in leadership skills within the CNRP as the top leader attempted “culture of dialogue” but individual law-maker attempted border scheme campaign against the vision of dialogue, or between President and Vice President, they both was likely not in the same page in directing their grand plan and their men. There were vacuum allowing external force to slow down or to obstruct the party’s works. There were encouragement for CNRP to work hard and to work smart indispensably after entering the Assembly. Actually, there were opportunities to change from within by working at the Assembly of those 55 law-makers, but their activities were active at the grassroots level more than in the top level of government. The chronic obstacles of democracy such as the court, the non-neutral national police institution, the systemic corruption, the unequal economic growth, the ineffective public servants, and the non-neutral army etc. were not actively engaged by or at least the CNRP’s working group did actively engage in policy changes of those shortcoming entities to survive itself or to assimilate them with their value for their long term “survival of the fittest” political arena.

the largest crowd of rally against election rigs in 2013 by the CNRP, the negotiation with Hun Sen seems achieved trivial things such as the new creation of NEC structure and the TV Channel, while the key components for power-based sustainability such as the reform or change of judiciary system/institution as well as the neutral arm-force, neutral policemen, and neutral public servants etc. were not prevailed. After agreeing to resume the national assembly and endorse Hun Sen as Premier in his fifth mandate, there were notably conflict in leadership skills within the CNRP as the top leader attempted “culture of dialogue” but individual law-maker attempted border scheme campaign against the vision of dialogue, or between President and Vice President, they both was likely not in the same page in directing their grand plan and their men. There were vacuum allowing external force to slow down or to obstruct the party’s works. There were encouragement for CNRP to work hard and to work smart indispensably after entering the Assembly. Actually, there were opportunities to change from within by working at the Assembly of those 55 law-makers, but their activities were active at the grassroots level more than in the top level of government. The chronic obstacles of democracy such as the court, the non-neutral national police institution, the systemic corruption, the unequal economic growth, the ineffective public servants, and the non-neutral army etc. were not actively engaged by or at least the CNRP’s working group did actively engage in policy changes of those shortcoming entities to survive itself or to assimilate them with their value for their long term “survival of the fittest” political arena.

This is perhaps one of the reasons in emerging Cambodia National Rescue Movement (CNRM) to replace some of the dysfunctional ability of this party. In practice, there are active unity and passive unity, active bonding and passive bonding, active splitting and passive splitting. This time, CNRP has been entrapped into a Khmer-pot (ក្អម), so if you don’t split your force (បំបែកំឡាំង) from such Khmer-pot, you will die effortlessly. Therefore, all splitting forces must come with pragmatic and concrete action-plans, vision, mission statement, and predictable outcomes etc.