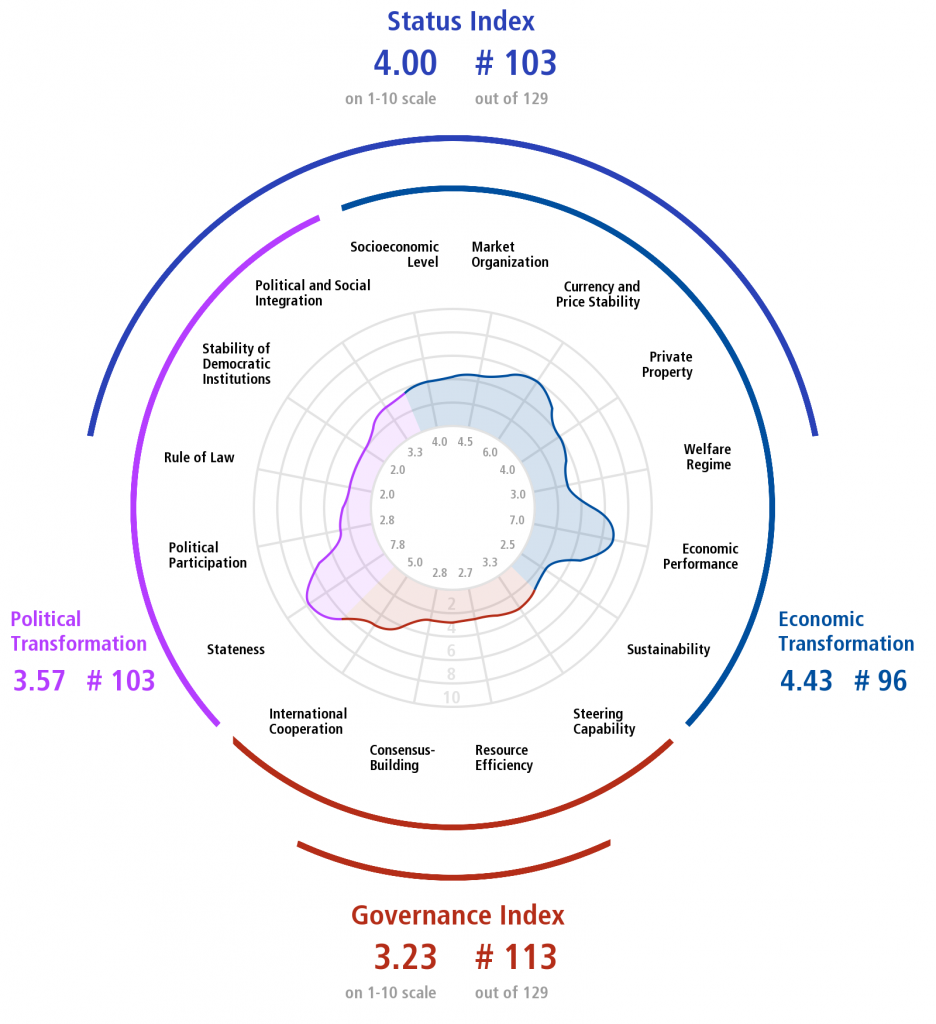

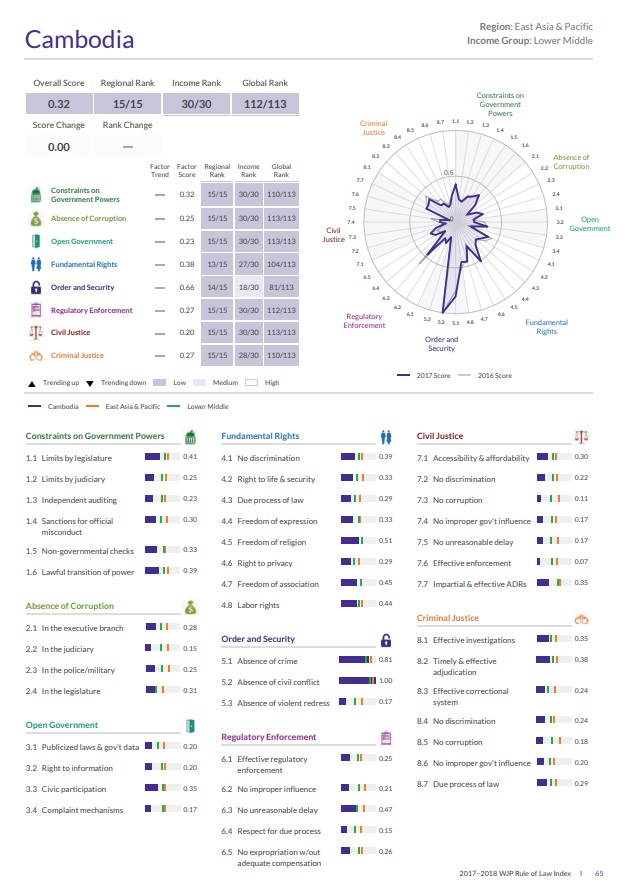

គំរោងយុត្តិធម៌ពិភពលោកបានរកឃើញចំណាត់ថ្នាក់យុត្តិធម៌និងនីតិរដ្ឋរបស់កម្ពុជាធ្លាក់ចុះខ្លាំងឆ្នាំ២០១៨គឺ១១២ក្នុងចំណោមប្រទេសទាំង១១៣។ ប្រទេសវេណេស៊ូអេឡាធ្លាក់ទាបបំផុតគឺ១១៣នៅពេលដែលកម្ពុជាបានត្រឹមវាយលុកយកឯកទកម្មទីពីរទាបបំផុតបន្ទាប់ពីប្រទេសវេណេស៊ូអេឡា។ ក្នុងចំណោមសុចនាករទាំងនោះ យុត្តិធម៌សុីវិល(civil justice)គឺមានកំរិតទាបបំផុត។

Cambodia

Op-Ed and Original Source for Reference: Key Page, PDF File, Interactive Page

Region: East Asia & Pacific

Income Group: Lower Middle

| Overall Score | Regional Rank | Income Rank | Global Rank |

| 0.32 | 15/15 | 30/30 | 112/113 |

| Score Change | Rank Change |

| 0.00 |

| Factor Trend | Factor Score | Regional Rank | Income Rank | Global Rank | ||

| Constraints on Government Powers | 0.32 | 15/15 | 30/30 | 110/113 | ||

| Absence of Corruption | 0.25 | 15/15 | 30/30 | 113/113 | ||

| Open Government | 0.23 | 15/15 | 30/30 | 113/113 | ||

| Fundamental Rights | 0.38 | 13/15 | 27/30 | 104/113 | ||

| Order and Security | 0.66 | 14/15 | 18/30 | 81/113 | ||

| Regulatory Enforcement | 0.27 | 15/15 | 30/30 | 112/113 | ||

| Civil Justice | 0.20 | 15/15 | 30/30 | 113/113 | ||

| Criminal Justice | 0.27 | 15/15 | 28/30 | 110/113 |

| Trending up | Trending down | Country | Low | Country | Medium | Country | High |

| Country | 2017-2018 Score | Country | 2016 Score |

| Country | Cambodia | Country | East Asia & Pacific | Country | Lower Middle |

| Constraints on Government Powers | |||

| 1.1 | Limits by legislature | 0.41 | |

| 1.2 | Limits by judiciary | 0.25 | |

| 1.3 | Independent auditing | 0.23 | |

| 1.4 | Sanctions for official misconduct | 0.30 | |

| 1.5 | Non-governmental checks | 0.33 | |

| 1.6 | Lawful transition of power | 0.39 |

| Absence of Corruption | |||

| 2.1 | In the executive branch | 0.28 | |

| 2.2 | In the judiciary | 0.15 | |

| 2.3 | In the police/military | 0.25 | |

| 2.4 | In the legislature | 0.31 |

| Open Government | |||

| 3.1 | Publicized laws & gov’t data | 0.20 | |

| 3.2 | Right to information | 0.20 | |

| 3.3 | Civic participation | 0.35 | |

| 3.4 | Complaint mechanisms | 0.17 |

| Fundamental Rights | |||

| 4.1 | No discrimination | 0.39 | |

| 4.2 | Right to life & security | 0.33 | |

| 4.3 | Due process of law | 0.29 | |

| 4.4 | Freedom of expression | 0.33 | |

| 4.5 | Freedom of religion | 0.51 | |

| 4.6 | Right to privacy | 0.29 | |

| 4.7 | Freedom of association | 0.45 | |

| 4.8 | Labor rights | 0.44 |

| Order and Security | |||

| 5.1 | Absence of crime | 0.81 | |

| 5.2 | Absence of civil conflict | 1.00 | |

| 5.3 | Absence of violent redress | 0.17 |

| Regulatory Enforcement | |||

| 6.1 | Effective regulatory enforcement | 0.25 | |

| 6.2 | No improper influence | 0.21 | |

| 6.3 | No unreasonable delay | 0.47 | |

| 6.4 | Respect for due process | 0.15 | |

| 6.5 | No expropriation w/out adequate compensation | 0.26 |

| Civil Justice | |||

| 7.1 | Accessibility & affordability | 0.30 | |

| 7.2 | No discrimination | 0.22 | |

| 7.3 | No corruption | 0.11 | |

| 7.4 | No improper gov’t influence | 0.17 | |

| 7.5 | No unreasonable delay | 0.17 | |

| 7.6 | Effective enforcement | 0.07 | |

| 7.7 | Impartial & effective ADRs | 0.35 |

| Criminal Justice | |||

| 8.1 | Effective investigations | 0.35 | |

| 8.2 | Timely & effective adjudication | 0.38 | |

| 8.3 | Effective correctional system | 0.24 | |

| 8.4 | No discrimination | 0.24 | |

| 8.5 | No corruption | 0.18 | |

| 8.6 | No improper gov’t influence | 0.20 | |

| 8.7 | Due process of law | 0.29 |