How China changed Sihanoukville

តាមអត្ថបទនេះ គម្រោងមហិច្ចិតាគំនិតផ្តួចផ្តើមផ្លូវសូត្រ(BRI)របស់ចិន កម្ចីគឺមានលក្ខណៈជាកិច្ចសន្យាគ្មានការស្មោះត្រង់(opaque contracts) អត្រាការប្រាក់ខ្ពស់ហួសហេតុ(exorbitant interest rates) ការផ្តល់កម្ចីដោយយកប្រៀបខ្លាំងលើម្ចាស់បំណុល(predatory loan practices) និងការឃុបឃិតគ្នាដោយអំពើពុករលួយ(corrupt deals)។ ជាលទ្ធផល ប្រទេសក្រីក្រជាច្រើននិងទន់ខ្សោយខាងស្ថាប័នល្អ(weak states and weak governance countries) មានបំណុលវ័ណកររើខ្លួនមិនរួមរហូតយល់ព្រមធ្វើសម្បទាលក់ឬប្រគល់ដីធ្លីក៏ដូចជាសម្បត្តិដាក់ចំណាំប្រកាន់ទៅអោយចិនទាំងដុលតែម្តង។ ចំណែកទេសចរណ៌និងវិនិយោគិនចិនវិញ និយមប្រើប្រាស់តែក្រុមហ៊ុនចិន សម្ភារៈចិន និងកម្មករចិន ដើម្បីទាក់ទាញយកលុយនោះទៅផ្តល់ផលប្រយោជន៌អោយចិនវិញ ទុកអោយប្រជាជនអ្នកមូលដ្ឋាននិងម្ចាស់ប្រទេសត្រដររស់តាមសម្មាអាជីវោខ្វះខាតដដែល។ គ្រាន់តែដើម៦ខែនៃឆ្នាំ២០១៨នេះ ជនប្រព្រឹត្តបទអាជ្ញាកម្មចិនដែលប៉ូលីសខ្មែរចាប់បានមានដល់៦៨ភាគរយនៃការចាប់សរុបទាំងអស់ទូទាំងប្រទេស។

Op-Ed: The ASEAN Post Team, 13 April 2019

Sihanoukville used to be a sleepy coastal town in south Cambodia. Its beaches were known for their quiet, cosy – albeit a little seedy – atmosphere that attracted mostly families, individual travellers and backpackers. Aside from the goings-on of the tourists and those connected with the country’s sole deep-water port, nothing much had changed over the years. That was until the Chinese investment flooded in as a result of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Cambodians Lose, As China Tourists And Cash Pour In

Fast forward to 2019 and the once-tranquil city has been transformed beyond recognition. Now an enclave of Chinese investment, Sihanoukville is peppered with Chinese-run, operated and patronised hotels, apartments towers, restaurants and gambling dens. The area is dotted with Chinatowns, festooned with neon signs in Mandarin which have taken the place of Khmer and English language signs.

The magnitude and make-up of its tourists has also changed with the new influx. Tourism increased more than 700 percent between 2012 to 2017, with Chinese tourists accounting for one-third of the 6.2 million visitors Cambodia received last year. Officials estimate that Chinese nationals make up some 90 percent of the expatriate population in Sihanoukville. A number of the long-term Western tourists living in the city have either been pushed or kicked out to make way for better paying Chinese. Some have moved out to avoid the area because of the loss of tranquillity.

Within the BRI framework, Sihanoukville is known as the first port of call on China’s massive infrastructure programme. The area, previously known as Kampong Som before it was renamed after former king Norodom Sihanouk, received US$4.2 billion in Chinese investment for power plants and offshore oil operations.

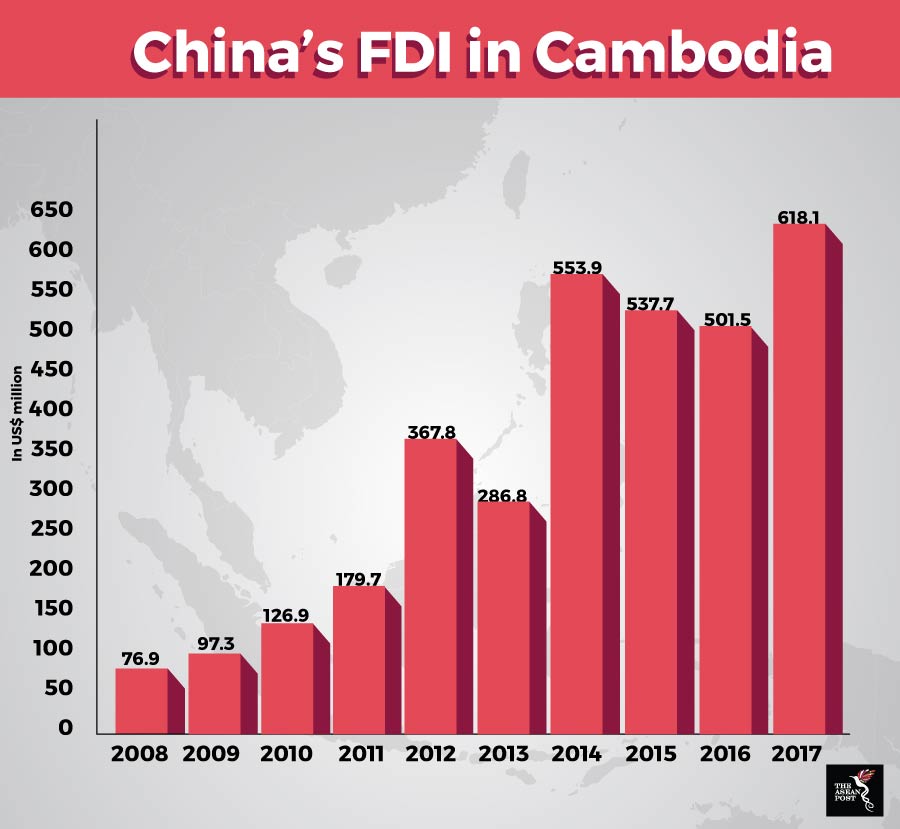

Beyond Sihanoukville, with the strong support of Prime Minister Hun Sen, the BRI has spread Chinese investment further inland into the kingdom. Cambodia is a key beneficiary of infrastructure projects under China’s trillion-dollar BRI, and this includes financing for new highways, national roads, power plants, airports, and special economic zones (SEZs) dedicated to technology innovations. China has also bequeathed US$100 million in aid to help modernise Cambodia’s military.

Chinese investment and related discontent

With the massive influx of Chinese investments, loans and aid, many have cautioned Cambodia on China’s debt-trap diplomacy. The Chinese loan model, often characterised by opaque contracts, exorbitant interest rates, predatory loan practices, and corrupt deals, has left smaller countries further debt ridden and in danger of losing their sovereignty.

The China Road and Bridge started construction of the country’s first highway last month, a US$2 billion four-lane road linking Sihanoukville and Phnom Penh. The growing dependence on China has led Hun Sen to insist that Cambodia is not a colony of China – going on to rubbish rumours that China plans to set up a naval base in the South China Sea, a strategic area which has long been an issue of contention between China and some ASEAN member nations.

The Chinese financial influx is also often ‘closed looped’, with few meaningful opportunities for local players. Chinese companies often do business with other Chinese companies, which then bring in Chinese workers. Chinese tourists, often travelling in groups handled by Chinese tourist agencies, want to stay at Chinese-run hotels and eat at Chinese restaurants, and local businesses and people are often forced out of any potential economic gain. The “Chinafication” of Sihanoukville has also stirred local resentment as more landless Cambodians are pushed out of Sihanoukville development deals while Chinese workers are brought in to cater to the growing demand.

Along with the steady influx of Chinese workers and visitors, is an increase in vices and criminal activities. In Cambodia, 68 percent of those arrested in the first six months of 2018 were Chinese citizens, far outnumbering others nationals. Demand from China and Vietnam has made Cambodia a key transit point in the illicit wildlife trade, with a record 3.2 tonnes of African ivory seized at the Sihanoukville port last December. Many Chinese nationals working as pimps and prostitutes in the seaside town have been arrested, and around 50 Chinese nationals were detained in Sihanoukville last August in a crackdown on prostitution rings. Chinese nationals, along with locals and other foreigners, have also been arrested during illegal drug raids on pubs.

Sihanoukville is a clear warning to all other investment destinations along the BRI route. While foreign aid and investment from China can benefit receiving countries who are often in dire need of investment and development assistance, their governments need to figure out how to balance this process without losing their national identities and sovereignty. Social and cultural impact assessments and studies, on top of environmental impact assessments, need to be undertaken to enable authorities to project and protect against the many negative impacts and changes.

Local or provincial authorities and communities, as well as other stakeholders, need to have a bigger say in how these Chinese investments are manifested, regardless of the pressure to comply from their leaders who are looking for a quick-fix for the national debt. If not managed well, BRI investments could result in the loss of identity and sovereignty for the host nation as it painfully morphs into another Chinese territory.

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 28 August 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related articles: