Cambodia’s Strategic China Alignment

A number of factors are driving Cambodia’s strategic convergence with China.

By Cheunboran Chanborey

July 08, 2015

Op-Ed: The Diplomat

According to conventional wisdom, the international system leaves small states less room for maneuver. Cambodia is no exception. Since the kingdom won its independence from France in 1953, it had been preoccupied with protecting that independence, as well as its sovereignty and territorial integrity. During the Cold War, Cambodian foreign policymakers tried various approaches, from neutrality to alliances with major power(s) and, worst of all, isolationism. Yet Cambodia remained a victim of power politics, and ended up with a civil war and some of the worst atrocities of the 20th century.

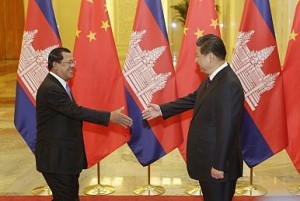

Early in the 21st century, China has emerged as a regional and global power. China’s power and influence can be felt in all corners of the globe, most evidently in continental Southeast Asia. In this context, the Cambodia-China bilateral relationship has experienced a remarkable transformation over the last decade or so. Although rooted in mistrust due to the involvement of China in Cambodia’s civil war and social strife, especially Beijing’s support for the Khmer Rouge regime, bilateral ties have noticeably consolidated and improved since 1997.

In December 2010, the two countries upgraded their bilateral ties to a ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Cooperation.’ Cambodia continues to attach great economic and strategic importance to China’s rise.

Economically, China plays an increasingly important role in the socio-economic development of Cambodia as its primary trading partner, largest source of foreign direct investment, and top provider of development assistance and soft loans. Noticeably, two-way trade between Cambodia and China grew from $2.34 billion in 2012 to around $3.3 billion in 2013. Recently, the two countries agreed to boost their bilateral trade to reach the target of $5 billion by 2017. Similarly, Chinese investment in Cambodia in 2013 rose 65 percent, to $435.82 million compared to $263.59 million in 2012. More importantly, Chinese loans and grants to Cambodia reached $2.7 billion in 2012, making it one of the latter’s largest donors. Moreover, Cambodia will reap enormous benefits from new Chinese initiatives such as the Maritime Silk Road and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Economically, China plays an increasingly important role in the socio-economic development of Cambodia as its primary trading partner, largest source of foreign direct investment, and top provider of development assistance and soft loans. Noticeably, two-way trade between Cambodia and China grew from $2.34 billion in 2012 to around $3.3 billion in 2013. Recently, the two countries agreed to boost their bilateral trade to reach the target of $5 billion by 2017. Similarly, Chinese investment in Cambodia in 2013 rose 65 percent, to $435.82 million compared to $263.59 million in 2012. More importantly, Chinese loans and grants to Cambodia reached $2.7 billion in 2012, making it one of the latter’s largest donors. Moreover, Cambodia will reap enormous benefits from new Chinese initiatives such as the Maritime Silk Road and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Militarily, China is the biggest source of assistance to Cambodia’s armed forces in various forms. In May 2012, Cambodia and China signed a military cooperation agreement in which China agreed to provide $17 million to Cambodia to build military hospitals and military training schools for the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces and promised to continue training military personnel in Cambodia. The latter is, according to Cambodian Defence Minister Tea Banh, a “great contribution to improving the Cambodian army’s capacity in national defense.” It is worth noting that Chinese military assistance increased remarkably at a time when Cambodia badly needed to build up its defense forces due to the increasingly tense border dispute with Thailand from 2008 to 2011.

Victim of Location

In geopolitical and strategic terms, Cambodia had been a victim of its location as a country sandwiched between two powerful and historically antagonistic neighbors, Thailand and Vietnam. The history of Cambodia vividly suggests that over the six hundred years following the fall of the Khmer Empire, Thailand and later Vietnam regularly defeated Khmer armies and annexed Khmer territories. The two countries had always attempted to impose their suzerainty over Cambodia. Cambodia’s acceptance of the French protectorate in 1863 was an escape from suzerainty.

The eruption of a border conflict with Thailand from 2008 to 2011 reminded Cambodian leaders that its stronger neighbors remain a security threat to the kingdom’s territorial integrity. It also prompted Cambodian leaders to rethink the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) role in maintaining peace and stability in the region. In fact, since becoming a member of ASEAN in 1999, the regional grouping has always been the cornerstone of Cambodia’s foreign policy. Cambodian policymakers were convinced that ASEAN would be a crucial regional platform through which their country could safeguard its sovereignty and territorial integrity as well as promote its strategic and economic interests. However, it seems that Cambodia’s confidence in ASEAN has faded due to the grouping’s ineffective response to the Cambodia-Thailand border dispute.

In geopolitical and strategic terms, Cambodia had been a victim of its location as a country sandwiched between two powerful and historically antagonistic neighbors, Thailand and Vietnam. The history of Cambodia vividly suggests that over the six hundred years following the fall of the Khmer Empire, Thailand and later Vietnam regularly defeated Khmer armies and annexed Khmer territories. The two countries had always attempted to impose their suzerainty over Cambodia. Cambodia’s acceptance of the French protectorate in 1863 was an escape from suzerainty.

The eruption of a border conflict with Thailand from 2008 to 2011 reminded Cambodian leaders that its stronger neighbors remain a security threat to the kingdom’s territorial integrity. It also prompted Cambodian leaders to rethink the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) role in maintaining peace and stability in the region. In fact, since becoming a member of ASEAN in 1999, the regional grouping has always been the cornerstone of Cambodia’s foreign policy. Cambodian policymakers were convinced that ASEAN would be a crucial regional platform through which their country could safeguard its sovereignty and territorial integrity as well as promote its strategic and economic interests. However, it seems that Cambodia’s confidence in ASEAN has faded due to the grouping’s ineffective response to the Cambodia-Thailand border dispute.

Most recently, Cambodia has had problems with its neighbor to the east, Vietnam, apparently due to sensitive issues related to border disputes and illegal migration, as witnessed by tensions that culminated in a violent clash on June 29, 2015 between Cambodian border activists and Vietnamese residents along the border. In an unprecedented move, Cambodia’s foreign ministry sent a dozen protest notes to urge Vietnamese authorities to halt all activities along the border that undermine the status quo.

Somewhat unusually, between July 2014 and June 2015, Cambodian authorities deported 2,058 illegal Vietnamese immigrants. Dynamic political developments in Cambodia in the aftermath of the July 2013 general elections – particularly the diffusion of the foreign policy-making process with the stronger influence of Cambodia’s opposition, a more vocal civil society voice in national politics, and the negative historical perception of Vietnam in Cambodia – play an important part in the prickly relationship. A general strategic misalignment between Phnom Penh and Hanoi is the underlying factor.

Regardless, while the reasons for the deterioration of Cambodia-Vietnam relations remain uncertain, it is certain that the more perceived unease or threat Phnom Penh has from its neighbors, the closer Cambodia will grow to China. This explains Phnom Penh’s inconsistency on the South China Sea, with its latest position actually that of Beijing.

Alternatives

Broadly, Cambodia might opt for alternatives by strengthening its relations with other major powers, such as Japan, India, and the United States. However, there are certain challenges and constraints for Cambodia in pursuing this approach. Japan has long been one of its most important development partners. However, the problem for Japan in the eyes of Cambodian foreign policymakers is that the former’s military and strategic role in the region is limited due to its pacifist constitution and perceived lack of a foreign policy independent from the United States.

As for India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Act East Policy sounds promising as far as India’s increasing engagement in Southeast Asia is concerned. However, there is a perception in the region that India still lacks both the capacity and the commitment to successfully implement its policy.

Broadly, Cambodia might opt for alternatives by strengthening its relations with other major powers, such as Japan, India, and the United States. However, there are certain challenges and constraints for Cambodia in pursuing this approach. Japan has long been one of its most important development partners. However, the problem for Japan in the eyes of Cambodian foreign policymakers is that the former’s military and strategic role in the region is limited due to its pacifist constitution and perceived lack of a foreign policy independent from the United States.

As for India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Act East Policy sounds promising as far as India’s increasing engagement in Southeast Asia is concerned. However, there is a perception in the region that India still lacks both the capacity and the commitment to successfully implement its policy.

Finally, although the United States has been playing a crucial role in maintaining and promoting peace and stability in Asia, there remains a huge gap in Cambodia-U.S. relations. The gap is the result of a strategic misalignment between the two nations, a trust deficit between the two countries’ leaders, and other sensitive issues hindering the bilateral relationship including the United States’ focus on human rights and democratic values.

Therefore, Phnom Penh might believe that a provisional alignment, rather than fully bandwagoning, with China is the best short-term strategic option given its security and development objectives. However, it is clear that Cambodia-China bilateral ties are asymmetric and the smaller side – Cambodia – will, to a certain extent, experience strategic risks and vulnerabilities. It might have to compromise its sovereignty and foreign policy autonomy to please China.

As a result, Cambodia must develop strategies for the medium and long terms. In the medium run, Cambodia must be a proactive member of ASEAN and play a role in promoting that organization’s centrality in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, Cambodia must create a favorable environment to consolidate its relations with other major powers in Asia and beyond.

In the long run, Cambodia must adopt a self-reliant and omnidirectional foreign policy. As a small state, Cambodia must seek a large number of friends in the region while maintaining the freedom to be itself as a sovereign, independent, and prosperous nation. Cambodia must promote a rules-based regional order so that all states, regardless of their size, approach international affairs with similar assumptions. It is key for Phnom Penh to ensure the equality and survival of small countries.

It is crucially important to emphasize that while there are different reasons Cambodia cannot execute all its strategic choices at the same time in the short run, the realization of the first option by no means affects the chance to implement the two other options.

Ultimately, Cambodia’s provisional alignment with China will depend on the foreign policy behaviors of Thailand and Vietnam toward Cambodia, ASEAN’s relevance in meeting the security need of its members, its capability to withstand perceived threats from neighboring countries, and the availability of sufficient support from the international community to ensure the small kingdom’s survival, sovereignty, and pursuit of prosperity.

The author is a PhD student at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, the Australian National University; and a research fellow at the Cambodian Institute for Strategic Studies (CISS).