សង្ខេប៖ អត្ថបទនេះរៀបរាប់ស៊ីជម្រៅពីនយោបាយបរាជ័យរបស់លោកហ៊ុន-សែន ម្តងហើយម្តងទៀតក្រោយឆ្នាំ២០១៣។ សមាជិកបក្សភាគច្រើនមិនសប្បាយចិត្តចំពោះលោកហ៊ុន-សែន ដែលពួកគេធ្លាប់តែសរសើរថាសម្រេចចិត្តត្រូវធ្វើត្រូវ តែពេលនេះបានធ្វើកិច្ចការមួយចំនួនធំដែលសមាជិកភាគច្រើនមិនគាំទ្រដូចជារំលាយគណបក្សសង្គ្រោះជាតិ ធ្វើជាបច្ចាមិត្រជាមួយអឺរ៉ុបនិងអាមេរិក បង្កើនបណ្តាញក្រុមខ្លួនលើកតំឡើងឋានន្តរស័ក្តិឆ័ត្រយោងព្រមទាំងគ្មានសមត្ថភាព និងហ៊ុមព័ទ្ធកេងចំណេញទ្រព្យធនសម្រាប់តែខ្លួននិងក្រុមខ្លួន។ ក្រុមដែលចេញមុខចំហរទប់ទល់នយោបាយខុសរបស់លោកហ៊ុន-សែនគឺស-ខេង។ យុទ្ធសាស្ត្រលោកហ៊ុន-សែនបំបែកកឹម-សុខាពីសម-រង្ស៊ី បានក្លាយជាការអោបយកកឹម-សុខា រួមរុញច្រានលោកសម-រង្ស៊ីអោយចូលជាធ្លុងមួយជាលោកស-ខេង។ គំរោងលោកហ៊ុន-សែនចង់ប្រកាសបន្តុបកូនខ្លួន បានបរាជ័យម្តងជាពីរដងទាំងផ្ទៃក្នុងបក្សទាំងឆាកអន្តរជាតិ។ ពត៌មានចចាមអារាមចុងក្រោយពីផ្ទៃក្នុងគឺការទាញយកលោកអូន-ពន្ធមុនីរ័តជាតំណាងនៅពេលលោកហ៊ុន-សែនមិនអាចបំពេញការងារបាន ដោយផាត់លោកស-ខេងចេញក្នុងហេតុផលថាទុកចាស់ៗមួយឡែកសិន ដោយអោយក្មេងៗគេធ្វើការម្តង។ អណត្តិលោកចូ-បៃដិន នឹងមានវិធានការជាក់ស្តែងដូចមានសំបុត្រពីសមាជិកព្រឹទ្ធសភាទាំង៨នាក់ស្រាប់ ដែលបណ្តាលអោយលោកហ៊ុន-សែនអង្គុយមិនជាប់ក្តិត បែរប្រើតុលាការកាត់ទោសមនុស្សម្តង១៥០នាក់ ហើយបានចាប់មនុស្សដាក់ពន្ធនាគារប្រមាណ៨០នាក់រួមទាំងព្រះសង្ឃ យុវជន យុវតី តារាចំរៀងរ៉ាប់ ក្មេងៗជាច្រើន។ ស្ថានការណ៍ដើមឆ្នាំក្រោយនឹងកាន់តែតឹងតែងខ្លាំងឡើយសម្រាប់លោកហ៊ុន-សែន ដែលការលេបត្របាក់ប្រជាធិបតេយ្យ ធ្វើអោយគាត់ឈឺជំងឺរលួយពោះវៀនយ៉ាងដំណំ បើមិនខ្ជាក់ចេញទេ គាត់នឹងស្លាប់។

Rumors have long swirled of an alliance between opposition leader Sam Rainsy and Interior Minister Sar Kheng.

By David Hutt November 27, 2020

Sam Rainsy has taken exception to journalists who write that he “fled” Cambodia in late 2015. Instead, he says, what actually happened was that Interior Minister Sar Kheng contacted him privately via then-U.S. Ambassador William Heidt to warn him not to return from a visit to South Korea. Rainsy has stated that Sar Kheng “begged me not to come back” and advised him to wait abroad as the Interior Minister tried to talk(calm?) Prime Minister Hun Sen down from his threat to issue an arrest warrant for the opposition leader.

The day Sam Rainsy was supposed to return from a visit to Seoul – November 16, 2015 – the National Assembly voted to remove his parliamentary immunity. At the time, he was president of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), the country’s only true opposition party. Banned in November 2017 on the spurious grounds that it was plotting a U.S.-backed coup, hundreds of the party’s elected officials and activists joined Sam Rainsy in exile, while the party’s president Kem Sokha, who took over the post in early 2017, was arrested for treason – a charge that still hangs over him.

Sam Rainsy’s telling of the events of November 2015 has been on the public record for almost two years, since he first made these claims back in January 2019. I cannot confirm all the details, but I hear they’re accurate. Speaking via email this week, Sam Rainsy elaborated. “I have spoken in private with [Sar Kheng]. I know his feelings and understand his fear of Hun Sen,” he told me, as I reported here. “Dissolving the CNRP might [have been] a pre-emptive move by Hun Sen to prevent an ‘alliance’ between Sar Kheng and Sam Rainsy,” he added. “Sar Kheng’s real but untold interest is to prevent Hun Sen from eliminating Sam Rainsy.”

Before the events of November 2017, Sam Rainsy told me, at least seven of the CPP’s 68 members of parliament “were pro-Sar Kheng” and, if instructed, could have joined with the CNRP’s 55 parliamentarians to create a majority in the National Assembly. “This helps explain Hun Sen’s fear and his determination to eliminate the CNRP under any ludicrous pretext such as ‘treason,’” he claimed.

Naturally, this raised more questions than it answered. Why, for instance, once it became apparent that Sar Kheng wasn’t able to tame Hun Sen, did Sam Rainsy not return, such as after attempts were made to arrest Kem Sokha in July 2016? (He was only formally exiled in October 2016.) One must also consider the political intention of his claims. For years, Sam Rainsy has tried to sow divisions between Hun Sen and Sar Kheng, who are thought to lead the two main factions within the long-ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), in much the same way as the prime minister has tried to widen splits within the CNRP.

Perhaps that was how Sar Kheng thought back in 2015 or even up until late 2017, but what about today? When asked about his current relationship with the interior minister, Sam Rainsy replied: “There are things on which we cannot elaborate at this point. Let’s avoid too much speculation. We will see.”

Since the 1990s, foreign diplomats and some of us hacks have portrayed Sar Kheng as the more amendable alternative to Hun Sen, as the Southeast Asia Globe documented in detail back in 2018. Indeed, the Phnom Penh grapevine echoed with claims that Sar Kheng was the only one capable of a “palace coup,” likely the only way of removing Hun Sen from office. But this always seemed to be one of those cases of actions being judged by reputation, not the other way around. And trying to identify divisions within the CPP has long been a unrewarding folly of Cambodia-watchers, a labor of judging whether jigsaw pieces of rumor and off-hand remarks fit neatly together.

Indeed, one might ask why Hun Sen in July made Chen Zhi, a Chinese-born, nationalized Cambodian businessman, his new advisor. Chen’s Prince Group conglomerate has become one of Cambodia’s largest firms in a very short space of time, despite questions over the sources of its capital. And as I wrote last month, there are even rumors in Washington that Chen has ties to the United Front Work Department, one of the Chinese Communist Party’s main agencies tasked with carrying out overseas foreign influence operations.

But Chen had been an advisor to Sar Kheng since mid-2017, with a rank within his Interior Ministry fiefdom equivalent to an undersecretary. Chen had even created a business that year with Sar Kheng’s son Sar Sokha, a secretary of state for Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport. So was this a move by Hun Sen to distance a powerful tycoon from Sar Kheng’s network or even to cut the Interior Ministry’s rumored back channel to Beijing?

The question that lingers on the edge of every probe into Cambodian politics is whether Hun Sen has complete authority within the CPP. This appears to be ever-changing, although the innumerable crises thrown up by 2020 seem to have put intra-party tensions on hold. I hear that Hun Sen’s long-standing ambition to hand over power to one his sons (likely the military’s de-facto chief Hun Manet, his eldest) has come up against opposition from the party in recent months and has now been shelved, awaiting more stable times.

Indeed, these aren’t good times for Hun Sen. Of course he isn’t to blame for the pandemic-induced economic crisis, though recovery will be hampered by his government’s economic policy over recent years, while the Cambodian leader is now busy trying to put out numerous other infernos created by his policy.

Cambodia faces backchannel pressure from its ASEAN partners, as indicated last month by Bilahari Kausikan, a former permanent secretary of Singapore’s Foreign Affairs Ministry, who pondered publicly whether Cambodia and Laos should be kicked out of the regional bloc because their foreign policy appears to be guided by Beijing – a claim that surely Kausikan isn’t alone in considering. Corruption proceeds are now drying up because of a decrease in Chinese investment, as well as the fact that (compared to investment from other Asian nations and the West) kickbacks from these projects tend only to go to the most senior Cambodian officials, not those lower-down the pecking order. This breeds resentment amongst party members.

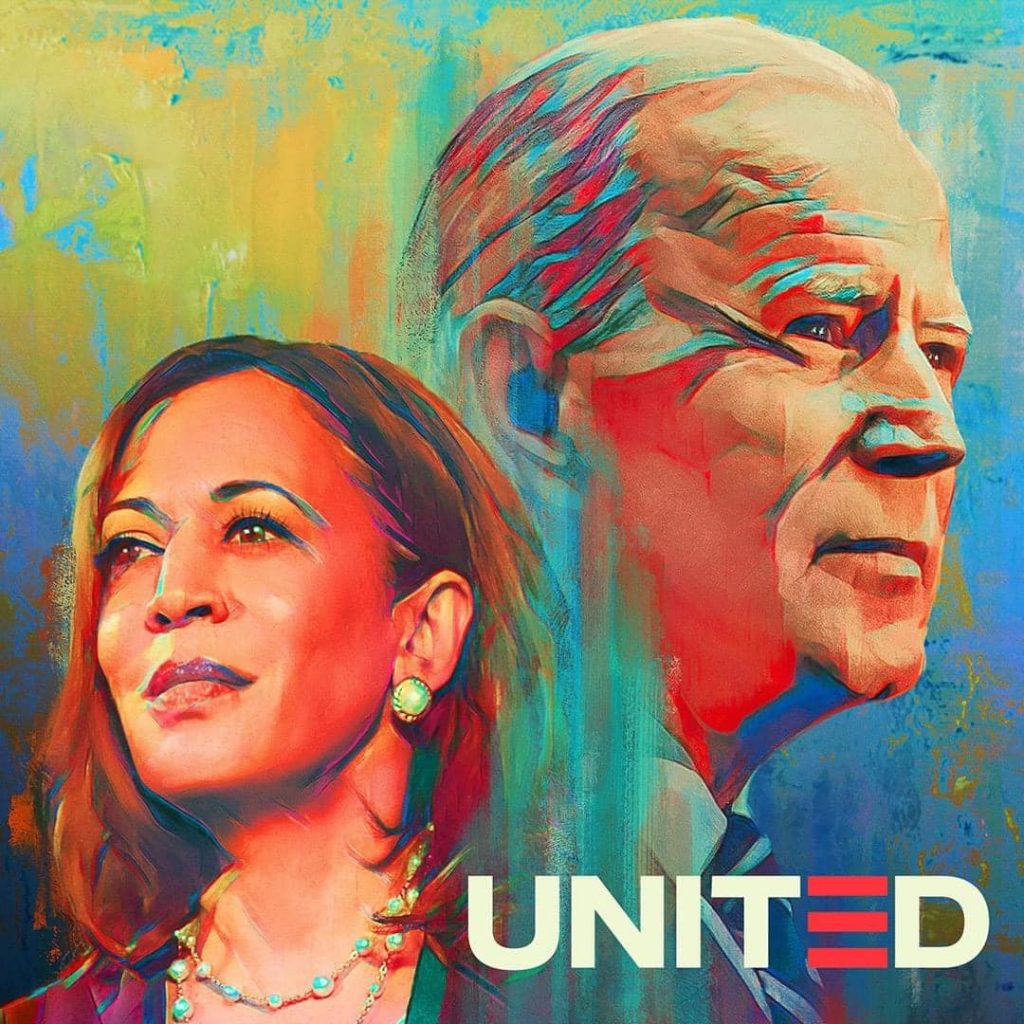

And the renewed threat of targeted U.S. sanctions, as called for by a group of American lawmakers this month, could see senior government and military officials, as well as ruling party-aligned tycoons, hit financially by Washington because of Hun Sen’s desire to stamp out all political opposition. This comes after claims that some CPP grandees wanted Hun Sen to do more to appease the European Union, but his refusal to do so ended up with Cambodia’s trade privileges being partly removed in August. (One imagines the same cohort of party grandees, possibly including Sar Kheng, are again pressing Hun Sen to seek conciliation with Washington.)

Naturally, there may be some within the CPP questioning the wisdom of Hun Sen’s leadership of late, which has careened from one crisis to the next, whereas in the past he seemed to have a natural talent for turning each possible disaster to his party’s benefit. That said, he has done more in recent years to make personal loyalty a determining factor of appointments, and the increasing common lash-out-at-any-critic style of nationalism fostered by Hun Sen has prompted more junior party and government officials to rally around the prime minister.

Hun Sen seems to be attempting a solution to the political void right now, but that involves first destroying the CNRP’s entire activist base (as with the mass trial of more than 100 CNRP members starting this week) before trying to turn Kem Sokha into a puppet figure of a feeble but legal CNRP. Next year we will find out if a rumored Hun Sen-Kem Sokha understanding goes the same way as the apparent Sar Kheng-Sam Rainsy entente.