Why There Won’t Be a Cambodian Spring This Election Year

Despite being well versed in the chaotic metropolises of South East Asia, I still found myself surprised by the coarseness of Cambodia’s capital city when I visited for the first time last month. Half-finished construction sites spill out into the roads, depriving pedestrians of footpaths and adding to Phnom Penh’s not-quite-finished character. Yet for the capital of a country that is now just three months away from a general election, there is a notable absence of the usual broad-faced men bearing grins and upwards pointing thumbs that you might expect to see postered to the sides of buildings and billboards. You may, in fact, be forgiven for not knowing that there is an upcoming election at all.

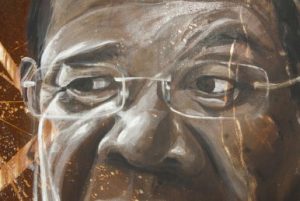

Cambodia’s leader, Hun Sen, is the world’s longest-serving prime minister having held the position since 1985. Rising to power as a battalion commander under the Khmer Rouge, he defected to Vietnam and became a leader of the rebellion against the regime before being appointed as deputy prime minister in the Vietnamese-installed government in 1979. Since then, Hun Sen has refused to relinquish power, and despite losing a UN-sponsored election in 1993 he went on to lead a successful coup against his co-prime minister, cementing his position at the head of the ever-incumbent Cambodian People’s Party (CPP). His reign has been characterized by the stifling of democracy and unabashed brutalizing of the opposition.

At the head of a government widely accepted as one of the world’s most openly corrupt, Hun Sen’s immediate family is known to have registered interests in over 114 domestic private companies, holding total or substantial control in 90 percent of them. These sectors span the breadth of the economy, from construction to hospitality, telecoms to media, and finance to mining. His relatives also hold key positions within the government and the military, increasingly embedding themselves into the country’s elite apparatus.

In the four years since there has been an undeniable systematic dismantling of the opposition party, and an intensified purge of government critics. With the assistance of the state’s judiciary, the party’s new leader Kem Sohka was arrested for treason in September 2017, while over 100 members of the CNRP’s leadership have been banned from participating in politics for the next five years.The only serious contender to have challenged the rule of the CPP was the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). Formed in a merger of two opposition parties and united under prominent reform campaigner Sam Rainsy, the party won a 44 percent share of the vote in the 2013 general election, nearly topping the CPP’s 49 percent. Despite Human Rights Watch supporting the CNRP’s accusations of electoral fraud, citing the registering of voters in multiple provinces and the issuing of fake election documents by the CPP, the incumbent government denied calls for an independent review into the election.

In November 2017, the Supreme Court officially disbanded the CNRP, eradicating the only serious contender in the upcoming general election and making the CPP’s landslide victory inevitable. The day was branded “The Death of Democracy” by the Phnom Penh Post, one of the only remaining English-language publication not closed down in recent years.

Sam Rainsy, who has been in exile since 2016 after being charged with defamation for accusing Hun Sen’s government of murdering the high-profile political activist Kem Ley, has since set up the offshoot Cambodia National Rescue Movement (CNRM) in an attempt to pull together an opposition ahead of the election. However, rather than uniting the opposition, this has further fractured relations with some adamant members of the disbanded CNRP who are opposed to the abandonment of their party. Many more are refusing to publicly support the new party in fear that their association could lead to their arrest if this party is targeted by the CPP too.

In this climate of intense frustration some commentators are questioning whether Hun Sen has gone too far, and in fact sealed his own fate by inciting a public uprising against the CPP. While others have underlined the claim that only 30 percent of the junior members of the armed forces now genuinely support the regime.

Yet while it is true that frustration is growing among Cambodian pro-democracy activists, there is no “Cambodian Spring” in the offing. Hun Sen’s position in the country has never been stronger; with no organized opposition to challenge him and near total de facto control of the judiciary, military, police force, and press.

I spoke to Dr. Sorpong Peou, a Cambodian-born Canadian professor at Ryerson University and an expert on politics and security in Cambodia, about the country’s immediate political outlook.

“My prediction is that anti-government protests and demonstrations are likely to develop as the July elections are fast approaching, but I don’t know if they will be sustained. The opposition, in my opinion, has weakened and will not be resilient. [Whereas] the CPP-led government is likely to use force to crush or thwart any movements seeking to challenge its power.”

When asked if he believed that Hun Sen could maintain power for the next decade, as he has stated his intention to, he told me there was no doubt about it. “Hun Sen cannot afford to lose because losing in Cambodia can mean the end, if not death.”

“The lack of legitimate state institutions has left Cambodia more or less in the Hobbesian ‘state of nature’, and the politics of survival remains intense. Thus, I don’t expect Hun Sen and his CPP to go down without a fight to the death. For me, this is the great Cambodian tragedy.”

Hun Sen has never been investigated by the International Criminal Court for his complicity in the Khmer Rouge regime and does not intend to stand trial either for the politically-motivated murders alleged against him since he has been in power.