THE DUMPLING SHOP OWNER AT THE CENTER OF AN AUTHORITARIAN CRACKDOWN

BY JUSTIN HIGGINBOTTOM

The experiment in democracy that is modern Cambodia seems to have hit a bump in the road. Actually, if Cambodian democracy were a car, it would be in a rice-field ditch and the villagers (and international observers) smelling smoke. Twenty-five years after the United Nations Transitional Authority ended its stewardship of the country, and despite having a new constitution, years of relatively free elections and billions of dollars in foreign aid, residents are effectively living under single-party rule. The question on people’s minds is what comes next — a tow truck or an explosion.

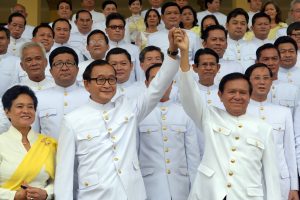

One interested observer is Sin Rozeth. The 34-year-old former commune chief and once rising political star was given the same choice as other members of the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party: defect to another party (preferably the ruling Cambodian People’s Party) or get out of politics. Rozeth chose the latter — she opened a dumpling restaurant in her old stomping grounds after the CNRP was forcibly dissolved in November — while looking for a way forward in the face of Cambodia’s increasingly totalitarian environment.

====

Mao Phally (Kampong Chhnang),

Siek Chamnab (Siem Reap), just mention a few, they are the future leader, the catalyst of change, and the agent of change, for Cambodia.

Rozeth opened a restaurant to support her mother, and to make up for the loss of her meager public salary. But her accusers say it’s a front for illegal political activities. “If this restaurant is used as a place to gather fire, it is really dangerous for Rozeth and it should not be tolerated,” Chheang Vun, a ruling party lawmaker, posted on Facebook. In response to claims that she’s harboring “rebels,” Rozeth hung a banner outside: “Rozeth’s shop welcomes all guests, but not rebels.” The tongue-in-cheek gesture earned her a reprimand by the city governor, who warned that using such language could damage the kingdom’s reputation. Rozeth says she feels threatened by the ongoing harassment, and a group of former CNRP members sent letters to several international bodies, including the United Nations Human Rights Committee, seeking help in pressuring the government to stop the “bullying.”

In the short term, at least, one-party rule will continue in Cambodia, says Sophal Ear, professor of diplomacy and world affairs at Occidental College. And mounting new opposition will be difficult. ”It’s like razing an old grove forest,” he explains. “You’re not going to get 100-year-old trees. You’ll have young trees, and they’ll be easy to bulldoze if they get too strong.” National elections are scheduled for this summer, and it’s unclear whether CNRP’s former supporters will turn toward another party or abstain from voting, says Sinthay Neb, director of the Advocacy and Policy Institute in Phnom Penh. Whatever happens, he believes the best way forward is for both sides to meet and work together — however unlikely.

For now, Rozeth refuses to give up: “As long as one still has breath, there is still hope for democracy.” She stays busy traveling to villages to perform charity work (this too, she says, is closely monitored). And she helps people who come to her shop, even if it’s only for a good meal.

Before I leave the noodle shop — which has filled with the evening crowd — I take a few photographs of the owner. Other patrons notice and pull out their phones. Seems they all want a selfie with the politician turned restaurateur now under fire.