Op-Ed: The Hindu

Political repression under Prime Minister Hun Sen has put the fragile democracy at risk

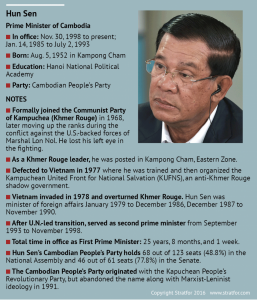

The crackdown in Cambodia is taking the form of criminalisation of the opposition and the media by Prime Minister Hun Sen ahead of the 2018 national elections. This slide into political regression is particularly troubling, as the country is still recovering from the memory of the genocide at the hands of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s. Cambodia has enjoyed relative prosperity in recent years thanks to the boom in garment exports and tourism; it can ill-afford political unrest. Its democracy too is a work in progress, and while the long-ruling Hun Sen has never been an ideal democrat, in recent years his autocratic tendencies have become increasingly more pronounced. The detention earlier this month of Kem Sokha, leader of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), on charges of treason, was accompanied by circumstances that led to the closure of an independent newspaper. In July, the government promulgated a law that enables the banning of political parties with connections to criminal convicts. Mr. Hun Sen, a former commander of the Khmer Rouge, whose lengthy rule since 1985 is often compared to the tenure of other dictators, is anxious to tighten his grip on the levers of power. Recently he declared his intent to carry on for another two terms. But it was the CNRP that made significant gains in the local body elections this June, even as the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) retained a majority of seats.

The crackdown in Cambodia is taking the form of criminalisation of the opposition and the media by Prime Minister Hun Sen ahead of the 2018 national elections. This slide into political regression is particularly troubling, as the country is still recovering from the memory of the genocide at the hands of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s. Cambodia has enjoyed relative prosperity in recent years thanks to the boom in garment exports and tourism; it can ill-afford political unrest. Its democracy too is a work in progress, and while the long-ruling Hun Sen has never been an ideal democrat, in recent years his autocratic tendencies have become increasingly more pronounced. The detention earlier this month of Kem Sokha, leader of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), on charges of treason, was accompanied by circumstances that led to the closure of an independent newspaper. In July, the government promulgated a law that enables the banning of political parties with connections to criminal convicts. Mr. Hun Sen, a former commander of the Khmer Rouge, whose lengthy rule since 1985 is often compared to the tenure of other dictators, is anxious to tighten his grip on the levers of power. Recently he declared his intent to carry on for another two terms. But it was the CNRP that made significant gains in the local body elections this June, even as the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) retained a majority of seats.

In his campaign during that election, Mr. Hun Sen barely concealed the instincts of a ruthless dictator when he openly threatened civil war in the event of the CPP losing the elections. Earlier, under its veteran leader Sam Rainsy, who is in self-imposed exile, the CNRP had challenged Mr. Hun Sen’s 2013 re-election and extracted major concessions at the end of a protracted political crisis. The allusion in the latest treason charge is to Mr. Kem Sokha’s comments before an Australian audience some years ago, pointing to the level of desperation in the ruling dispensation. The current political turmoil in Cambodia reflects an ongoing shift in international influence in the decades following the genocide. The U.S. had been closely involved in the restoration of democratic stability in the country, and the Cambodian turnaround is one of the United Nations’ great success stories. But recent years have seen a dramatic rise in Beijing’s bilateral and regional engagement with Phnom Penh, which under Mr. Hun Sen is using the great power rivalry to evade accountability by his regime. Cambodia’s cancellation of the annual joint military exercises with the U.S. this year coincided with the first such engagement with China, underscoring the extent of the changing dynamics of big power diplomacy in Southeast Asia. The ‘America First’ approach under President Donald Trump is not likely to alter this trend. It is left to the international community to keep a sustained focus on Cambodia, and underline how precariously placed the Cambodian recovery still is.