Op-Ed: The Guardian

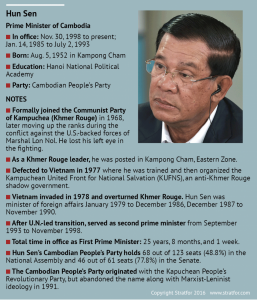

Cambodia’s Hun Sen is one of the world’s longest standing leaders. His party has been happy to hold elections as long as it knows it is going to win, and to embrace underhand tactics or outright force when things don’t go quite as planned. Another poll looms next year and, after more than three decades in his post, the prime minister and former Khmer Rouge commander says he has decided to continue for 10 more years to ensure stability.

Voters seem less keen on his unending tenure – and the Cambodian People’s Party knows it. A gradual expansion of space for civil society, activism and political activity went into reverse after the opposition united and did better than expected in 2013’s poll. The process accelerated last year as the CPP grew more nervous. It suffered again in this year’s local elections. It has overseen strong growth and reduced inequality. But there is widespread anger over rampant corruption and land grabs. An overwhelmingly young and increasingly urban population, more knowledgeable and sophisticated than their parents thanks to city life, social media and travel, feel they owe the government little.

Now the government has charged opposition leader Kem Sokha with treason, punishable by up to 30 years in jail, and has threatened to dissolve the Cambodia National Rescue Party if it does not disown him. He is accused of plotting with the United States to topple the government. Hun Sen’s real concern is clear and – as the previous opposition leader Sam Rainsy could testify – the tactics look awfully familiar.

Meanwhile, independent media have been silenced: a staggering $6.3m tax bill forced the Cambodia Daily to close , and radio stations carrying programmes from Voice of America and Radio Free Asia were shut down for supposed technical and administrative violations. Attacks on NGOs are intensifying.

The real shift in Cambodia is towards less western involvement, not more. The economy has grown and aid flows have diminished, reducing the government’s need to placate western donors. Meanwhile, China has pumped up aid, trade and investment without airing inconvenient human rights concern. These dynamics are evident elsewhere – look at the Philippines, Thailand or Myanmar– and the environment for human rights defenders is increasingly grim. The Trump administration’s lack of interest in human rights and own authoritarian tendencies fuel the long-term trend.

Some hope the CPP may yet pull back a little having made its show of strength. Pressure from diplomats has had some effect in the past. But the broad tendency across the region is undeniable and alarming.

The crackdown in Cambodia is taking the form of criminalisation of the opposition and the media by Prime Minister Hun Sen ahead of the 2018 national elections. This slide into political regression is particularly troubling, as the country is still recovering from the memory of the genocide at the hands of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s. Cambodia has enjoyed relative prosperity in recent years thanks to the boom in garment exports and tourism; it can ill-afford political unrest. Its democracy too is a work in progress, and while the long-ruling Hun Sen has never been an ideal democrat, in recent years his autocratic tendencies have become increasingly more pronounced. The

The crackdown in Cambodia is taking the form of criminalisation of the opposition and the media by Prime Minister Hun Sen ahead of the 2018 national elections. This slide into political regression is particularly troubling, as the country is still recovering from the memory of the genocide at the hands of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s. Cambodia has enjoyed relative prosperity in recent years thanks to the boom in garment exports and tourism; it can ill-afford political unrest. Its democracy too is a work in progress, and while the long-ruling Hun Sen has never been an ideal democrat, in recent years his autocratic tendencies have become increasingly more pronounced. The